On a planet 71% covered by water and with 10% of the land under ice, we are all dependent on the ocean and the cryosphere, says the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which reminds us that water and ice are in balance, “interconnected with other components of the climate system through global exchange of water, energy and carbon.” Climate change is disrupting this equilibrium. Glacier loss is a common phenomenon, but there is one mass of ice that scientists have been watching with concern for decades: Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier. Its critical nature as a kind of ticking time bomb of global warming has earned it the popular nickname “doomsday glacier”.

Antarctica is such a hostile place that it was not explored and conquered until the early 20th century, although the mapping of its surface, about 97.6% of which is covered in glacial ice, only began in the middle of the century. But that ice does not stand still: most of the glaciers flow into the sea, forming tongues that help to stabilise them, and occasionally break off to form floating icebergs. West of Antarctica is one such glacier, first sighted in 1940 by Richard Byrd’s third expedition, identified in 1947, and mapped between 1959 and 1966. In 1967 it was named after the late glaciologist Fredrik T. Thwaites.

The impact of global warming

Thwaites is not just any glacier: it is the widest on the planet, some 120 kilometres across and covering an area of 192,000 km2, larger than the US state of Florida. At the so-called grounding line, the boundary between the ice resting on land and that floating on the sea, it is between 800 and 1,200 metres thick, and is flowing into the ocean at a rate of about two kilometres per year. The ice discharges into Pine Island Bay in the Amundsen Sea, along with that from the neighbouring Pine Island Glacier, the fastest moving glacier on the entire continent and the world’s largest sea ice discharger, responsible for a quarter of Antarctica’s ice loss.

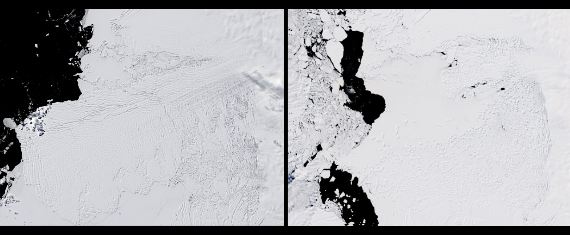

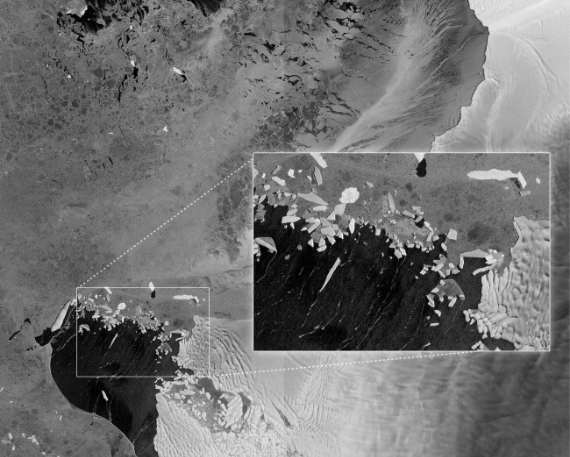

As it empties into the sea, part of Thwaites Glacier is plugged by an ice shelf that is 45 kilometres wide and about 587 metres thick. This shelf occupies only part of the front of the glacier; the rest is a floating tongue of ice that once formed a compact mass, but in the second decade of this century broke up into separate icebergs held together only by the mass of sea ice.

This means that the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers play a major role in the state of the land ice, and are among the most vulnerable to global warming. Thwaites has been retreating for centuries, a process that began to be accentuated in the 1940s by the El Niño phenomenon. According to the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a project co-funded by the US and the UK, the amount of ice discharged into the sea has doubled over the last 30 years; each year it loses 50 billion tonnes more ice than it receives from snowfall. Since 2000, it has lost more than a trillion tonnes, and its height is shrinking by one metre a year.

A chain reaction

The consequences of all this ice loss don’t just affect Antarctica: the melting of Thwaites is responsible for 4% of all global sea level rise. But if it were to disappear completely, global sea levels would rise by 65 centimetres, which is why it is dubbed the “doomsday glacier” in the media. Ella Gilbert, a climate scientist at the University of Reading, puts it in context: “There’s been around 20cm of sea-level rise since 1900, an amount that is already forcing coastal communities out of their homes and exacerbating environmental problems such as flooding, saltwater contamination and habitat loss.”

This collapse will not happen overnight, but according to British Antarctic Survey geophysicist Fausto Ferraccioli, “some models suggest that this could happen comparatively quickly, within a few centuries.” At the current rate, by the end of this century, the melting ice from this glacier will cause sea levels to rise by several centimetres.

The big threat is that warm water from the Amundsen Sea will flow under the ice, eroding it, loosening it from the bedrock and accelerating its movement. This, in turn, will allow the warm water to reach other inland ice, causing, according to Gilbert, “a regional chain reaction and drag other nearby glaciers in with it, which would mean several metres of sea-level rise.” The effect is accelerated by geothermal springs beneath the glacier. The presence of cracks in the ice shelf also affects its stability, so much so that, according to Oregon State University glaciologist Erin Pettit, it could “shatter like a car windscreen” within the next decade.

Stop the ice melting

In the face of these great dangers, great remedies are being proposed. University of Lapland glaciologist John Moore has previously proposed building a 100-metre-high wall on the seabed to stop the ice melting in Greenland, or 300-metre-high artificial islands to plug the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. His new idea is to install giant underwater curtains 100 kilometres long, anchored to the seabed, to prevent warm water from reaching Thwaites.

At an estimated cost of $50 billion for such a major geoengineering project, it seems almost impossible. But Moore and his collaborators at Cambridge University, who are currently testing the idea with 1-metre-long curtains in laboratory tanks, are designing a prototype to be tested in the River Cam in 2025, and then a larger 10-metre curtain in a Norwegian fjord. If the initial results are encouraging, the project may go ahead.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication