Although the fight against pseudoscience is as topical today as it ever was, there was a time when the distinction between science and myth or superstition was so blurred that great scientists often dabbled in the latter: Isaac Newton, for example, was a seasoned alchemist who believed in dragons. In the 17th century, pioneers like the Italian Francesco Redi began to debunk some long-held pseudoscientific myths, such as spontaneous generation. Around the same time, a Danish physician and scholar called Ole Worm lived, and we have him to thank for debunking one of the greatest myths of all time: the existence of unicorns.

Ole Worm, known by his Latinised name Olaus Wormius (13 May 1588 – 31 August 1654), could be said to have lived the privileged life of those who could devote themselves to study and knowledge without the inconvenience of having to earn a living. His grandfather was a Lutheran magistrate who fled to Denmark from the Catholic-dominated Netherlands. His son was mayor of the Danish city of Aarhus and had a fortune that enabled his son Ole to travel around Europe, studying in Marburg, Basel, Padua, Paris and elsewhere.

He obtained his doctorate in medicine in Basel in 1611 with a thesis on One Hundred Medical Controversies, practised medicine in London, and finally settled in Copenhagen in 1613, where he taught Greek, physics, medicine and natural philosophy, was dean of the University of Copenhagen and personal physician to King Christian IV. His marriage also came about because he was chosen by his friend, the mathematician Thomas Fincke, as a husband for one of his daughters, Dorothea. His main academic contributions were in embryology—the small irregular bones that some people have between the sutures of the skull are named after him—and above all in the study of the runic alphabet and the texts and stelae written in it, including early Scandinavian literature.

Curiosity gabinet

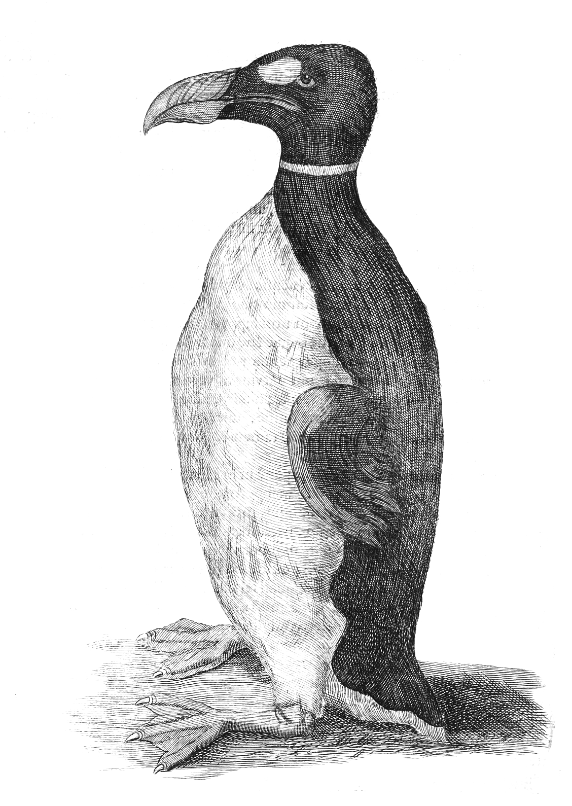

But the great work he created during his lifetime was something that was very much in vogue among the wealthy scholars of the time: his curiosity cabinet, the Museum Wormianum, a vast collection of all kinds of specimens of nature and ethnographic artefacts. His massive 400-page catalogue, published in four volumes the year after his death, included such rarities as the only known natural representation of a living giant auk, the original Arctic penguin, now extinct; the animal that served as the model was Worm’s own pet.

As a scientist working at the time of transition between classical knowledge and empirical science, Worm set out to disprove some of the beliefs of his time, which now seem laughable: with an accurate illustration of a bird-of-paradise, he proved that these birds had legs. The arrival in Europe of dead specimens prepared by indigenous people of New Guinea, who had torn off their legs, had led to the belief that these were animals from the biblical paradise that never touched the ground and simply flew around until they died; this is reflected in the scientific name of the species, Paradisaea apoda or “legless bird-of-paradise.” Worm also concluded that lemmings were rodents, not born from the air by spontaneous generation.

Another myth that Worm helped to dispel was that of the most popular fantastical creature of all time, including the present day. Although the origin of the unicorn legend is uncertain, such was its hold that it survived for millennia, with numerous descriptions, illustrations and even instructions on how to hunt it with the help of a fair maiden to appease its ferocity and wildness, as explained by Leonardo da Vinci. The pharmacopoeia of the time included unicorn horn, also known as alicorn, which in powdered form was a costly product attributed with healing properties and as an antidote to poison.

Worm’s cabinet included a suspected unicorn horn, but also a narwhal tusk still attached to the animal’s skull. The two appendages were exactly the same, so in 1638 the scholar argued that unicorn horn powder was actually narwhal tusk powder; unicorns, he concluded, did not exist. It is said that Worm may have had a non-altruistic interest in this, as his in-laws—the Bartholin family of doctors and scientists—were in the business of selling narwhal horn as a superior remedy. It is perhaps for this reason that Worm, in fact, tested narwhal horn powder on animals as an antidote to poison and found that it worked. Despite the merit of these early pre-clinical trials, it is clear that the results were flawed, as narwhal horn has no healing properties either.

Worm died in 1654 because of his selflessness: during a bubonic plague epidemic in Copenhagen, he continued to care for the sick. The plague killed him. But interest in his life and work has endured through the centuries: the great horror writer H. P. Lovecraft, creator of the Cthulhu Mythos universe, credited a certain Olaus Wormius with the translation from Greek into Latin of the Necronomicon, his fictional Book of the Dead, although he placed it in the 13th century. Ironically, the name of the Danish myth-buster is now associated with one of the most popular myths in literature.

Comments on this publication