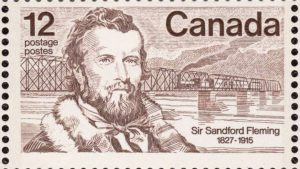

While we work, the other side of the world sleeps. Our lives are governed by the clock. But for all of us to organise our daily activities around a common timetable, someone had to get us all in sync. In 1876, Sandford Fleming (7 January 1827 – 22 July 1915), a Scottish-born Canadian engineer and inventor, missed his train because of a time mix-up. What would have been a trivial anecdote to anyone else was, for him, the motivation for an endeavour that would eventually synchronise the world’s clocks.

Until the end of the 19th century, there was no universal zero meridian. The Earth’s equator, an imaginary line, is a specific geographical location, a circle halfway between the North and South Poles. Lines of latitude, also called parallels, are determined by the geometry of the planet. This is not the case with meridians, which are arbitrary; there is no objective reason to locate the zero meridian in any particular place. In 1851, the British astronomer George Airy proposed that it should be that of the Greenwich Observatory, which was already in use in Britain. But prior to the International Meridian Conference held in Washington D.C. in October 1884, different countries used different meridians of zero longitude, usually in relation to their own capital cities.

This lack of a common reference of longitude prevented the standardisation of time around the world, so each country set its own time without coordination with others. Nor, of course, did the technology exist to give everyone access to a common time reference. In 1847, when a standardised train timetable based on the Greenwich meridian was legislated in Great Britain, the General Post Office telegraphed a signal to the various stations to set their clocks.

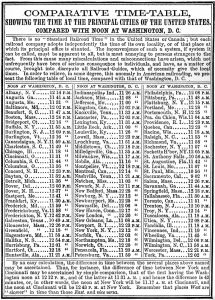

But in a large and dispersed country like the USA, things were more complicated: a table published in 1857 in Dinsmore’s American Railroad and Steam Navigation Guide and Route Book shows more than a hundred local timetables that varied capriciously not in hours, but in minutes. When it was noon in Washington, it was 12:08 and 11:48 in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, both in Pennsylvania; 9:02 a.m. in Sacramento, California; and 12:42 in Frederickton, New York. Railway companies used local timetables in their offices, and in the absence of a standard timetable this led to missed connections and inconvenience for travellers. The same was true for navigation, so the first International Geographical Congress, held in Antwerp in 1871, recommended the universal adoption of the Greenwich meridian.

The unique time system

It was in this context that Fleming found himself travelling in Ireland in 1876. By then he was a mature man of recognised stature. Having emigrated to colonial Canada at the age of 18, he was the engineer responsible for thousands of kilometres of railway in his adopted country, had mapped uncharted territory, designed Canada’s first postage stamp and co-founded two scientific institutions. It was on that trip to Ireland that he missed the train due to a mix-up in the timetable between AM and PM. And that mishap is credited with being the moment when Fleming decided it was time to put an end to the world’s time chaos.

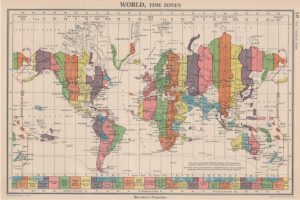

Fleming’s proposal was to divide the Earth into 24 time zones, each covering 15 degrees of longitude and named by the letters of the alphabet from A to Y, excluding J, so that the time in each zone would be unique and all would refer to the Greenwich G meridian. In 1876 he published a booklet entitled Terrestrial Time in which he explained his idea. In reality, Fleming’s proposal was different from what we now understand as universal time: his “cosmopolitan” or “cosmic” time was intended to be the same everywhere on the planet. For example, if it was 21:30 in Greenwich, that time would be valid everywhere in the world as G:30, although in each country it could be translated locally as 22:30, 23:30 and so on. Clocks, Fleming proposed, would have two dials showing the local numerical and alphabetical 24-hour time; he had a double-sided watch built as an example.

Fleming’s unique time system, which did not formally establish a zero meridian, never came to fruition. The engineer himself later proposed a modified version that used the Greenwich meridian as zero longitude and its anti-meridian—longitude 180—as the line marking the change of day. Fleming’s work, which he championed at several conferences, had a major impact on governments and the scientific community. The International Meridian Conference of 1884 finally established Greenwich as the reference for longitude and time, but did not impose the zones delimited by Fleming, as it was considered that this should be left to each country to decide.

It took several more decades for the world to adopt worldwide standard time, but today Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), based on the Greenwich meridian, recalls Fleming’s legacy, especially in its military version, Zulu Time, which uses an alphabetical code. The Canadian engineer, a restless man, continued until his death to promote a wide variety of initiatives, from undersea telegraph cables to land policy, from business ventures in cotton, cement and coal to recreational interests in horticulture, curling and mountaineering. He was certainly a man who made good use of his time.

Comments on this publication