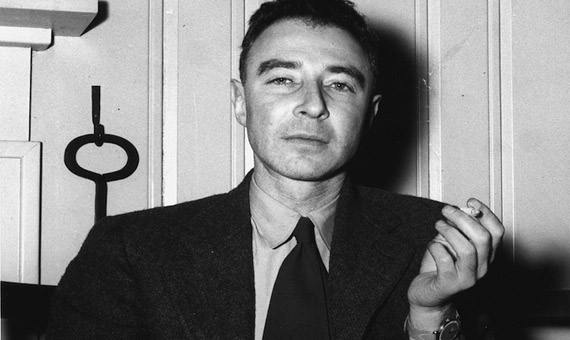

The Manhattan Project took shape in the first half of the 1940s as the United States sought to build the world’s first atomic bombs, which would ultimately be dropped on Japan in 1945. This momentous project was carried out at various facilities across the United States, involving thousands of people and a huge investment. As part of this macro project, a secret facility was built at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the bombs were finally assembled. This particular project involved many scientists recruited by the project leader, physicist Robert Oppenheimer. Most of these scientists were prominent physicists, chemists, mathematicians, computer scientists, engineers… all of whom were directly involved in the construction of the bombs. However, Oppenheimer also recruited various lesser known scientists to study and monitor the possible effects of the radioactive elements that made up the bombs. Among them were physicians and biologists, including the director’s own wife.

PHYSICIANS

Louis H. Hempelmann (1914-1998) was primarily responsible for the radioactivity-related medical studies and procedures carried out at Los Alamos. He was recruited by Oppenheimer in 1943 at Berkeley, and although the Manhattan Project’s brigadier general, Leslie Groves, did not consider it necessary, Oppi would go on to hire him.

There, Hempelmann would first undergo in-depth training as a radiologist before developing procedures for the proper handling of uranium, plutonium and polonium. He also developed a swab test for detecting radioactivity in the nose and tests to detect radioactivity levels in urine. He was thus able to regularly screen the scientists and technicians who worked on site and found no significant effects… that is, until a number of accidents occurred, more precisely three of them—one in 1944 involving plutonium and two others involving polonium, one in 1945 just before the bombs were dropped on Japan, and the other a year later in 1946. Hempelmann was involved in all three by administering various medical treatments, although the last two ultimately ended in the death of the two scientists concerned. He would continue to monitor the health of some 30 workers who were in the vicinity of the accidents until the 1990s. On these he published a series of papers in which he claimed to have found no signs of an increase in cancers(1). According to his studies, they had died of normal, age-related diseases.

Notably, Hempelmann was involved in the lead-up to the experimental bomb test, code-named Trinity, that took place in 1945 near Los Alamos, by issuing warnings about the possible influence of prevailing weather conditions. Hempelmann, alongside physician James F Nolan (no relation to the director of the recent Oppenheimer movie), whom he had hired to take charge of the general medical treatment of the residents there, issued several reports before and after this test—which had remained top secret until recently—exposing its inherent dangers, sometimes in stark contrast to others who attempted to downplay the risks(2).

While Hempelmann’s work at the Los Alamos facility came to an end in 1948, he would continue to be involved in the atomic tests carried out by the United States in the Pacific. He would later become a professor of radiology. In fact, he was the first person to warn of the negative effects of using a device, namely the fluoroscope, which uses radioactivity to study organs in movement(3) and which was being used indiscriminately to measure the size of children’s feet in order to make appropriate footwear for them.

WOMEN BIOLOGISTS

Several female biologists worked with Hempelmann at the Los Alamos facility, including Oppenheimer’s own wife, Katherine Puening, who ran blood tests at the facility for at least a year. Many scientists came to Los Alamos along with their families. Their wives were also encouraged to get involved. For example, Hempelmann’s wife worked as a secretary at the medical department, alongside Enrico Fermi’s wife. Local biologists such as Floy Agnes Lee were also recruited. She was a native American who also happened to be a biologist. She would study the blood of workers in general and especially those scientists who suffered accidents. Her work would later focus on analyzing the effects of radiation on chromosomes.

A leading biologist, Linus Pauling, whom Oppenheimer had tried to recruit to Los Alamos, refused to go. While some authors have claimed that he did this for personal reasons—because of Oppi’s alleged dalliances with his wife—it probably had more to do with his opposition to the use of nuclear bombs. In fact, after Pauling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954 for his studies on chemical bonding, he was awarded the Peace Prize in 1962 for his peace activism.

There was also another distinguished biologist, Hermann Müller, who, although he was not at Los Alamos, played an active role in the discussions that took place in the United States over the use of atomic bombs. Müller was perhaps the most qualified US biologist for such discussions, as in the late 1920s he had discovered that X-rays produce mutations in fruit flies. Müller would later travel to Europe in the 1930s, first to Germany and then to Russia, for both personal and political reasons. He would ultimately leave both countries due to political or scientific issues (Hitler, Stalin, Lysenko…) and finally ended up in Scotland—with a short stay during the Spanish War—where he would continue his research on the mutagenic effects of radiation. From there, before the outbreak of the Second World War, he would return to the United States in the early 1940s to take part in the scientific discussions on bombs: from 1943 to 1946, first as a consultant to the Manhattan Project, then to the Nuclear Energy Commission. Although his position was not well known—it was all top secret—in both cases it must have been exceedingly high up. In fact, almost 20 years after his first experiments, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1946, all but confirming the pivotal role he played. And thereafter he would always oppose the use of atomic bombs by signing important documents against their use alongside other Nobel laureates.

Last but not least, there was a further scientist who entered Los Alamos as a physicist—a “hard scientist”—but who left as a biologist—a “soft scientist”. His name was Leo Szilard, a Hungarian-German physicist who emigrated from Germany first to England and then to the United States after Hitler’s rise to power. When he arrived in the States, it was he who penned the letter (also signed by Einstein) warning US President Roosevelt that the Germans had achieved nuclear fission. This 1939 missive prompted the rapid development of the Manhattan Project and the construction of the Los Alamos facility. There, Szilard would play an active role in building the bombs. However, he clashed several times with General Groves and with Oppenheimer himself over the prospect of actually using the bombs in the war and specifically against Japan, with Germany already defeated and the Japanese almost defeated. So at the end of the war Szilard forsake his career as a physicist and “switched” to molecular biology. Notably, he helped develop techniques to achieve the cloning of cells for the first time and he was also an active researcher on bacteria and viruses and even invented apparatus to cultivate them in the lab. It was another sad case of a physicist who, upon seeing the consequences of the atomic bombs, would turn his back on physics to embrace biology, with another example being prominent biophysicist Francis Crick.

Manuel Ruíz Rejón

University of Granada, Autonomous University of Madrid and co-author of the book La Herencia del Mendelismo

Bibliography

(1) Voelz, GL Hempelmann, LH, et al. 1979. A 32-year medical follow-up of Manhattan Project plutonium workers. Health Phys. Oct: 37(4), pp.445-485.

(2) On the page of the National Security Archive: 78th Anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings: Revisiting the Record – Documents of Hempelmann and Nolan.

(3) Hempelmann, Louis H. 1949, “Potential dangers in the uncontrolled use of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes”, New England Journal of Medicine, 241(9): pp. 335-336.

Comments on this publication