It seemed like a good idea: to design a machine that would reinvest in itself the energy it produced in order to keep moving, so that once started it would run indefinitely, providing free energy forever. However, even in ancient times there were enlightened minds who sensed a trap, even if they couldn’t quite put their finger on it. By the 19th century, thermodynamics had explained why perpetual motion, or perpetuum mobile, is simply a physical impossibility, incompatible with the laws of nature.

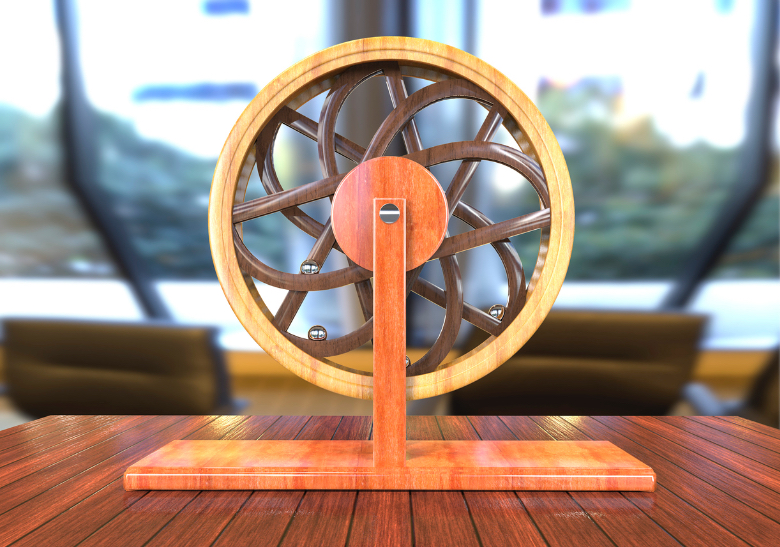

In the mid-12th century, the great Indian mathematician and astronomer Bhāskara II designed a wheel with curved spokes partially filled with mercury. As the wheel turned, the mercury would move from one end of the spokes to the other, keeping the wheel in constant motion as one heavier side would drag the other lighter side. Bhāskara’s wheel, a hypothetical design, is often cited as the first documented case of a perpetual motion machine, although its design was actually a modification of an earlier one described in the seventh century, and some authors place the earliest such idea in the West in the first century AD.

The search for the moto continuo

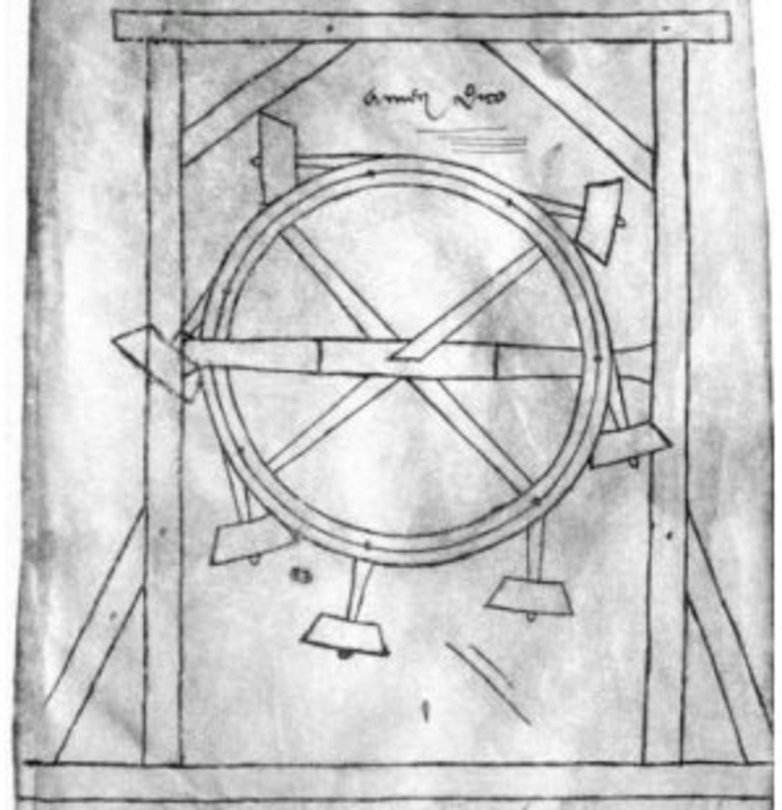

As the historian Lynn Townsend White Jr. has written, in India the concept of perpetual motion “was consonant with, and was probably rooted in, the Hindu belief in the cyclical and self-renewing nature of all things.” In the West, when the idea began to gain momentum in the 13th century—also the time of the first Arabic writings on the subject—the inspiration was a hybrid of the divine and the human: since God had achieved perpetual motion of the celestial bodies, why not try to discover and exploit the secret? In the West, the first design is attributed to the Frenchman Villard de Honnecourt, whose work is known only from a book of drawings in which, around 1230, he depicted a wheel similar in principle to that of Bhāskara, but replacing the mercury with weights, a recurring theme in later versions.

In the centuries that followed, many attempts were made with wheels, clocks, magnetic spheres, Archimedes’ screws, windmills, watermills… Leonardo da Vinci doubted the feasibility of the moto continuo, but produced several designs of hydraulic systems and ball-weighted wheels, coming to the conclusion that the idea could not work; in one of his writings he scornfully exclaimed that the promoters of these machines and their “vain designs” should go and keep company with the “seekers of gold,” the alchemists. Galileo, for his part, did not work on the idea, but his notes reveal that he did not believe in the concept because he sensed that it violated the laws of nature.

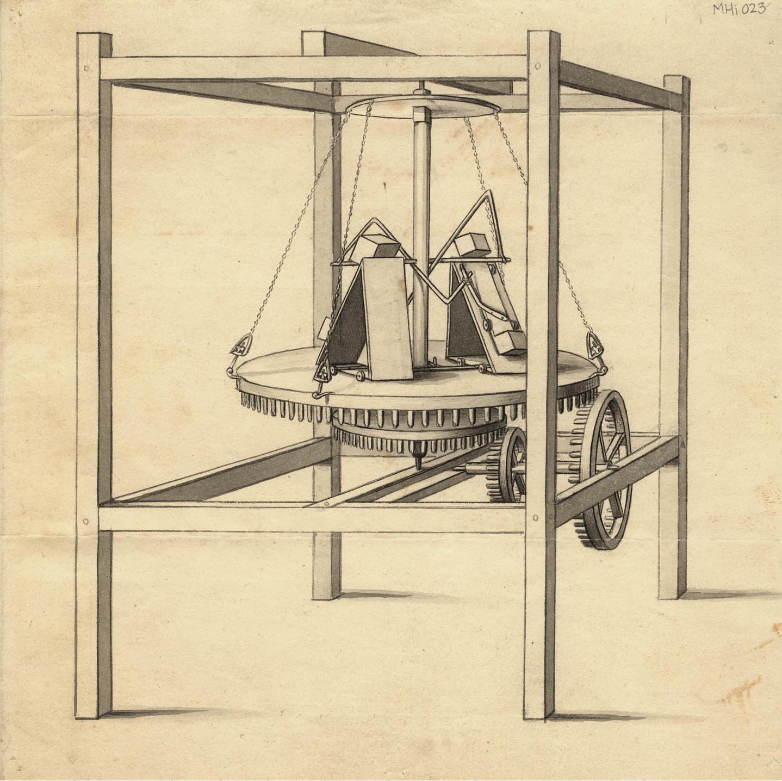

Nevertheless, the idea of perpetuum mobile seduced renowned scientists such as Robert Boyle—with his “self-filling flask”—Johann Bernoulli and even Nikola Tesla. During the 17th and 18th centuries, inventors such as Robert Fludd and Johann Bessler “Orffyreus”, among many others, constructed clever designs for machines that could run for a long time, but not perpetually. In 1775, the French Academy of Sciences stopped accepting proposals for such machines in view of the failures. There were also resounding frauds; in 1812, the American Charles Redheffer profited by exhibiting a perpetual generator that could power other machines. Robert Fulton, who is credited with developing the first steamboat, exposed the hoax: from an upstairs room, an old man operated a crank connected to a hidden cord.

A machine of the third kind

It was not until the second half of the 19th century that the laws of thermodynamics, the joint work of several scientists, put the nail in the coffin of these machines. According to the first law, the energy of an isolated system is constant—it is neither created nor destroyed—so it is not possible to extract more from a system than it consumes without additional input. According to the second law, entropy always increases; energy is lost in the form of heat through friction and other phenomena. Perpetuum mobile violates either the first law of thermodynamics (perpetual motion of the first kind, requiring no external energy) or the second law (perpetual motion of the second kind, converting all heat into usable mechanical or electrical energy), or both. But these are inviolable laws.

And what about a perpetual motion machine of the third kind, with zero friction and in a perfect vacuum without producing any usable energy? It won’t work either; atoms in motion dissipate their energy over time. Superconducting materials, with zero resistance, require more energy than they produce. What are often presented as perpetual motion machines have a flaw or a trick: the drinking bird uses the energy from the evaporation of water, and stops when it runs out. A machine gun uses the fuel of gunpowder; the cartridge belt of bullets always comes to an end, so it is no different from the fuel tank of a car. Certain machines use external solar or radioactive isotope energy, which is also consumed; contradicting the classics, the motion of the heavens is not eternal: spinning/orbiting objects in the vacuum of space do dissipate energy, but very slowly.

All this has not stopped countless inventors from pursuing, even in the present day, what is a physical inconsistency that does not work even when dressed up in advanced new physics: recently, the concept of time crystals, materials that were originally attributed with an atomic oscillation in a ground state that was likened to a tiny perpetual motion machine, has created controversy among physicists. But the concept also fails the test and has been reformulated to fit the accepted laws of physics; unfortunately, as Galileo warned, “it is impossible to deceive nature”.

Comments on this publication