Humans have had a complicated relationship with our diversity as a species. And while one might think that the virtual disappearance of the term “race” in favour of the more neutral “ethnicity” is a response to social etiquette, it is actually something deeper: the concept of race makes no sense from a genetic point of view. But this does not require us to deny our diversity, provided we understand that it is quite small and manifests itself in very different ways from what is commonly believed.

The idea of races is so ingrained in our perception of humanity that it existed as far back as ancient Egypt, where Egyptians distinguished themselves from Nubians, Libyans and Asiatics. It continued in classical Greece, where Aristotle wrote that northern Europeans were full of “spirit”, but were deficient in intelligence and skill, and so lacked political organisation; the peoples of Asia were the opposite, and so were in “continuous subjugation and slavery”. The Greeks, of course, possessed all the virtues.

If Aristotle could perhaps be called one of the first racists on record, it must be understood that racism was part of mainstream thinking for most of history, and was used to justify slavery. Figures admired today were ardent racists: Voltaire argued that dark-skinned people were a different species, and the philosopher Immanuel Kant called them “vain and stupid”, capable only of learning how to be enslaved.

Darwin’s gradualism

Charles Darwin’s role was somewhat more complex and ambiguous. In modern times it has been pointed out that he supported the abolitionist movement, and that he correctly deduced, against the trend of his time and that of other scientists such as Alfred Russel Wallace and Ernst Haeckel, that all human beings had a common origin and formed a single species. But to portray him as an enemy of racism would be illusory: he envisaged a racial hierarchy that regarded other non-European peoples as savages and inferiors at earlier stages of human evolution, to be exterminated and replaced by the “civilised races”. Contrary to the thinking of his time, however, Darwin understood that race was a quagmire, with some proposing as many as 63 different races. He did, however, contribute one important idea: gradualism in the characteristics of populations.

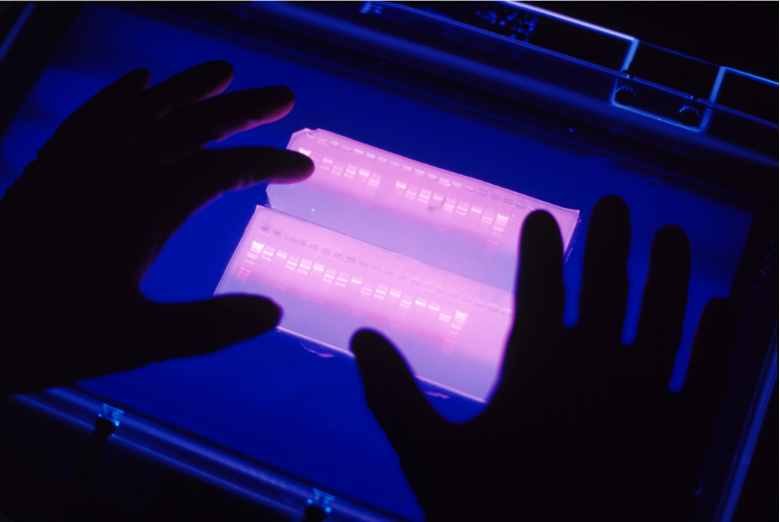

It was only in the 20th century that it became clear that behind the most obvious characteristics traditionally used to define races, such as skin colour, eyes, hair or facial features, there was a more complicated reality. In 1972, the geneticist Richard Lewontin published a study that analysed differences between “races” in 17 markers, including blood proteins, and concluded that 85% of the variation was between individuals within the groups themselves, 8% within populations within the same race, and less than 7% between them. In other words, individual variation was far greater than that separating these theoretical races, supporting Darwin’s gradualism. Many other studies came to similar conclusions, bolstering an idea proposed by the anthropologist Ashley Montagu in 1942: that races are a social construct with no genetic basis.

The impact of social determinants

The sequencing of the human genome at the beginning of this century put the nail in the coffin of the idea of race: humans share 99.9% of our DNA. And, confirming the findings of Lewontin and others, of the 0.1% that differentiates us, almost 96% corresponds to variations between individuals of the same “race”, and only 4% to differences between groups. But even in the latter case, these groups are not the obvious ones, such as skin colour.

Some confusion may have been caused by the genetic ancestry tests so popular today: when the results report that the user has 12% Scandinavian or 23% Persian in their genes, it could be understood as meaning that a person’s genome is made up of different components with different ethnic proportions, like the ingredients of a sauce. This is not the case: these analyses are based only on that very small part that differentiates us; and although specific geographical origins are proposed for some variants, experts stress that they are much more diluted and uncertain than the companies selling the tests would have us believe.

Nevertheless, these differences, however small, do exist. But as Harvard University geneticist David Reich explains in his book Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (Oxford University Press, 2018), the populations differentiated by these variations are not those identified by racial stereotypes.

His work has shown, for example, that what we would call the “white race” arose from the mixing 10,000 years ago of four populations as different from each other as today’s Europeans and East Asians; or that the increased risk of prostate cancer attributed to African Americans lies in one small place in the genome, but that African Americans who inherited these particular genes from European ancestors are spared this risk. In fact, other studies have found that when social determinants are removed, many of the differences often attributed to ethnic groups disappear. The bottom line is that races are created by us, not by nature.

Comments on this publication