This century has seen a new word enter the environmental vocabulary: microplastics. Marine biologist Richard Thompson of Plymouth University first used the term in 2004, in a study that revealed the abundance of microscopic plastic fragments in the oceans. We now know that they are a pollutant that reaches every corner of the planet. More worryingly, recent studies have shown that microplastics are already inside us, in our tissues and organs. And we don’t yet know the extent of their toxicity.

As defined by organisations such as the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) or the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), microplastics are those smaller than five millimetres, about the size of a pencil eraser. Primary microplastics are those that are deliberately manufactured at this size. They are found in many products, including cosmetics, clothing, fertilisers, detergents and paints. Interestingly, the largest source of this contamination in the EU is the infill material on artificial turf sports pitches. Secondary microplastics, on the other hand, are those that are generated by the breakdown of other plastics.

According to data from various studies by the European Environment Agency, 2-4% of the world’s plastic production, between six and 15 million tonnes, is dumped into the environment every year; of around three million tonnes of primary microplastics, half end up in the oceans. More than 14 million tonnes have already accumulated on the world’s ocean floor, but there is no place they haven’t invaded, from the atmosphere to the poles, on mountaintops and in deep ocean trenches. Their presence is so ubiquitous that, according to one study, they are penetrating pre-plastic lake sediments, making their presence no longer a suitable geological indicator of the Anthropocene, the human era.

From food to brain

The findings of other studies are even more alarming. Microplastics can be found in the air, in water, in food and drink packaging, and in the food chain: they can be ingested by marine organisms, but they are also absorbed from the soil by plants and passed on to the animals that eat them. A study by the University of Victoria (Canada) attempted to estimate the amount of microplastics that enter our bodies, an arduous task. The authors calculated that we ingest up to 52,000 particles a year through 15% of our caloric intake alone, rising to 121,000 in the air we breathe. But they admit that this is an underestimate, and that the real total is probably in the range of hundreds of thousands. Or much higher: another study by Trinity College Dublin estimates that babies can ingest a million particles a day from plastic baby bottles, where they are released when heated.

In 2018, up to nine types of microplastics were detected in human faeces for the first time— including those of babies—and were found to be more prevalent in people with inflammatory bowel disease, especially where symptoms are more pronounced. However, if they were excreted in the same way as they are ingested, this would be less of a concern. But this is not the case: we absorb them. Studies have found microplastics in human blood, placenta, breast milk and various organs. And because we breathe them in, they also penetrate deep into our lungs.

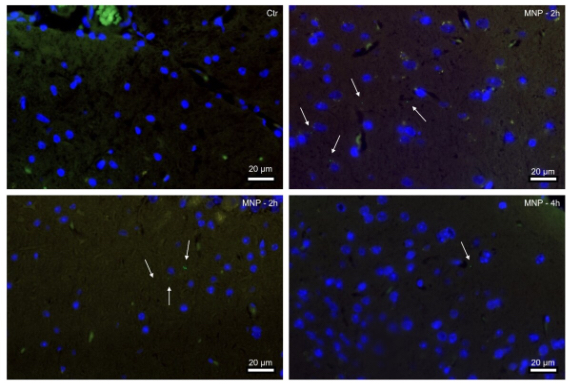

Even more striking are the results obtained by a group of researchers from the Medical University of Vienna, the Medical University of Debrecen in Hungary and other institutions when they orally administered micro- and nanoplastics—those smaller than 0.001 millimetres—to a group of mice: only two hours after ingestion, these materials were found in the animals’ brains. Other similar studies have confirmed the presence of microplastics in the brains of mice and their spread throughout the body.

But since the brain is protected by the blood-brain barrier, which filters what enters from the blood, much like the strict security check at an airport, how do microplastics manage to get through? It has been suggested that certain molecules in the environment can strongly bind to plastic particles, forming what is called a corona. Researchers have found that particles of a certain size with a corona of cholesterol—an essential lipid in cells—could cross the barrier.

Effects still unexplored

Against this background, the impact of microplastics on the body is still largely unexplored. Their effects can be both physical, through the particles themselves, and chemical, through the substances that plastics contain as additives—such as endocrine disruptors—and even infectious, through micro-organisms attached to the plastic. The effects could include oxidative stress and inflammation, which are linked to cancer, as well as cardiovascular disease and other illnesses. A link has been found between the presence of microplastics in arterial plaque and an increased risk of heart attack or stroke.

According to the co-leader of the Austro-Hungarian study, Lukas Kenner, “in the brain, plastic particles could increase the risk of inflammation, neurological disorders or even neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.” Neurocognitive changes or deficits in learning and memory have been found in the mouse studies mentioned above, although this does not necessarily apply to humans.

So how can we reduce our intake of microplastics? According to the Canadian study, one measure that can help is to drink tap water instead of bottled water—which is also better for the environment: bottled water adds 90,000 microplastics to the usual intake, compared to only 4,000 in tap water. But for the authors of the study, more radical measures are needed: “If the precautionary principle were to be followed, the most effective way to reduce human consumption of microplastics will likely be to reduce the production and use of plastics.” As for baby bottles, the authors of the Irish study recommend not warming milk in the bottle, but in a non-plastic container.

Comments on this publication