The scale of the current pandemic began to become more apparent when the world’s leading power, the United States, exceeded 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 at the end of May. That official figure, not yet reached by any other country in the world, could be considerably lower than the actual number of deaths according to studies that estimate 50% more deaths in the most affected areas. While in countries such as Spain the political opposition accuses the government of hiding the true death toll, the truth is that such a count is almost impossible to make accurately.

In addition to uncontrollable factors, such as patients who die without being diagnosed, there is the complexity of collecting and processing this data. These difficulties, which are inherent in any epidemic, are multiplied in the case of a pandemic. It was even more complicated a century ago, when in the midst of the 1918 flu pandemic an unknown American official found a scientific method to learn the actual number of deaths, a feat for which Wade Hampton Frost is beginning to be recognised as one of the fathers of epidemiology.

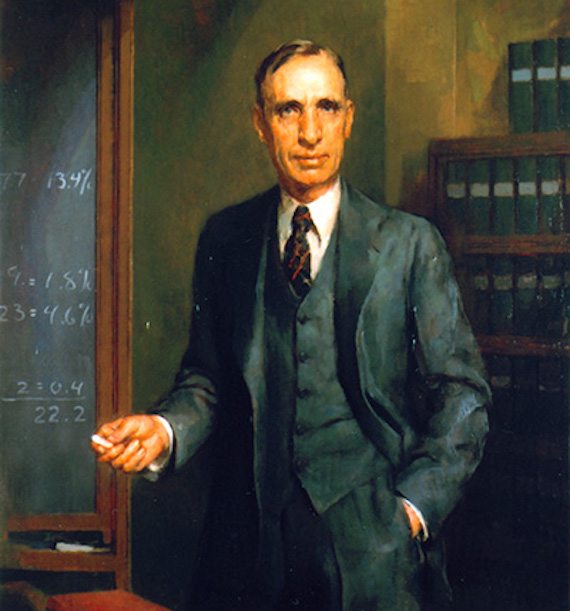

Little is known about the life of Wade Hampton Frost (3 March 1880 – 1 May 1938) up to that crucial moment, except that he was the son of a rural doctor from the interior of the state of Virginia and was home-schooled by his mother. After following his father’s vocation and finishing medical school —with an emphasis on mathematics and clinical analysis skills— he entered the U.S. Public Health Service in 1906 and was sent to New Orleans to fight an outbreak of yellow fever. His team managed to control that outbreak, the last one of that disease recorded in the United States. After that success, Frost was promoted to work at the National Public Health Laboratory. There, he focused on investigating the horrific polio outbreaks that suddenly paralysed and killed children in a particular area, and he discovered that one of the keys to these seemingly unpredictable outbreaks was that many children could be infected by the virus but remain asymptomatic, silently transmitting the illness to others.

A strange pattern in the most virulent flu

Wade Hampton Frost was continuing with this work when, in the fall of 1918, the drastic increase in flu deaths led to the closure of schools on the east coast of the United States, the saturation of hospitals and a daily death toll that made headlines. The high number of deaths overwhelmed the ability of health officials to count them, especially in the most populated urban areas, while medical care in rural areas was marginal. Moreover, the electron microscope had not yet been invented; so there was no way of detecting something as small as a virus, and without any diagnostic tests many cases of this particularly aggressive flu were mistaken for cases of pneumonia.

To track the progress of the pandemic in his country, Frost and his colleague Edgar Sydenstricker designed a large national health survey. House-by-house, and following a statistically representative sample, the interviewers managed to fill out some 113,000 questionnaires, which collected the age and sex of all the tenants in each house, as well as the date and duration of any possible cases of pneumonia or flu, whether mild, severe or fatal.

Thanks to this macro-survey, Wade Hampton Frost discovered a strange pattern of mortality in the 1918 flu. Unlike seasonal flu, which particularly affected children and the elderly, this new flu had a much higher mortality rate in young adults (under 40). Frost went further and invented a method for analysing the survey data in an effort to know more accurately how many people had died from the pandemic. He could have considered his 1918 data accurate enough, but decided to compare them to mortality rates from influenza and pneumonia from previous years, which served as the basis for a “normal” mortality pattern throughout the year: 1.5 deaths per 1,000 population in a typical influenza season, compared to 5.5 in the pandemic autumn of 1918.

The problem of indirect deaths

This was the first time that the excess mortality method, now a classic in epidemiology, was used. According to Frost’s calculations, the difference in that wave of the pandemic was four more deaths per thousand inhabitants throughout the United States, a figure that served to better evaluate the impact of the second wave of the 1918 flu than the official death toll, given the different levels of reliability of those data depending on the geographical area.

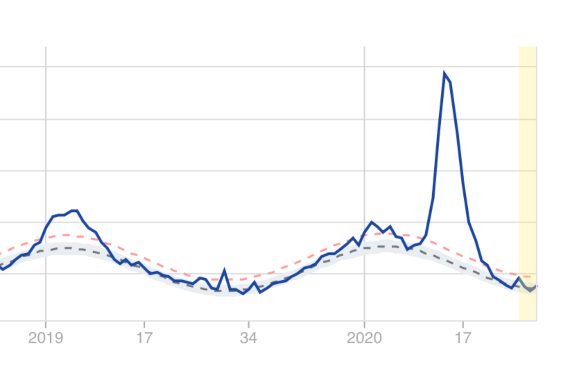

Frost’s method is used today by both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its European counterpart (the ECDC). Early estimates of excess mortality at the onset of the current pandemic in the US detected 57% more deaths than the officially confirmed deaths from COVID-19. However, it should be noted that these general estimates also include deaths indirectly caused by the pandemic, such as those of people who suffered a heart attack and did not seek health care quickly enough because they were confined; or patients with different ailments who could not be well cared for in hospitals overwhelmed by the pandemic; or those who died due to the physical and mental consequences of social distancing and confinement.

Frost’s excess mortality method gives us a more accurate measure of the overall impact of a pandemic, as opposed to imperfect systems for counting those who died from the disease. “We’re not going to know the true number of deaths from COVID-19 until the dust settles,” epidemiologist Daniel Weinberg at Yale University recently told National Geographic. Statistically combining the data from both methods (number of confirmed deaths and excess mortality) over the next few years will lead us to estimate a total number of deaths from COVID-19, which will be the one that finally makes it into the history books.

Comments on this publication