The COVID-19 pandemic has raised public awareness of the risk of infectious outbreaks. Among the potential threats that have hit the headlines since then is avian influenza, also known as bird flu, which can infect humans with a high mortality rate and which it has been said could cause the next pandemic. But is the risk high?

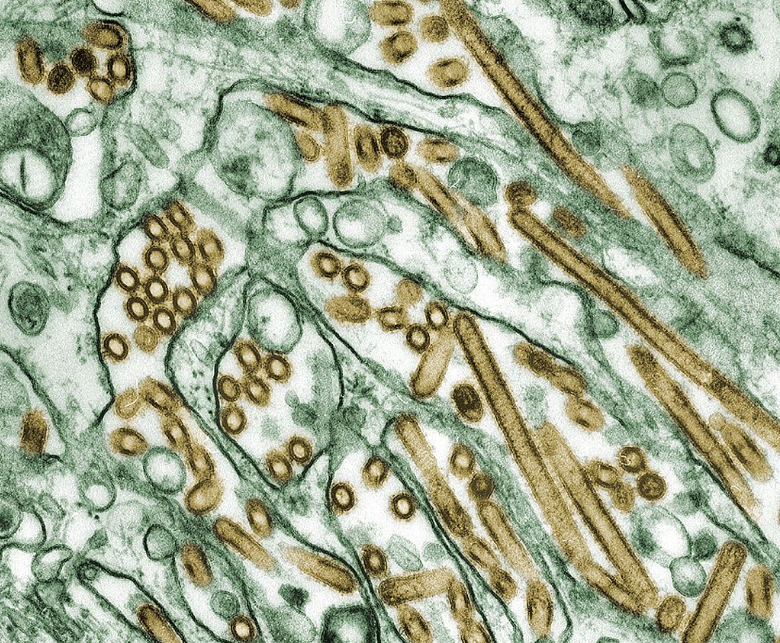

Influenza viruses have an RNA genome that is split into several pieces, making it easy for new variants to emerge. There are four genera, A to D. Influenza A is classified into subtypes depending on two of its proteins: haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). What we know today as avian influenza is an influenza A virus subtype H5N1 adapted to birds, but which can cause zoonosis, or jump to humans.

The current lineage was isolated on a goose farm in China in 1996, although the virus has been recognised as a disease of birds since the 19th century. It can be airborne, but bird-to-bird transmission is mainly by contact and contaminated water. The first human outbreak occurred in 1997 in Hong Kong, affecting 18 people and causing six deaths. In 2006, the first human-to-human transmissions were reported in north Sumatra, where eight members of a family were infected, seven of whom died.

Numerous outbreaks of the virus have occurred in animals, which have intensified since the emergence of a new variant in 2020. In 2022, 67 countries reported outbreaks in poultry or wild birds, with more than 131 million birds killed by the virus or by preventive culling. The virus has also been detected in at least 26 mammalian species in 10 countries, including farmed mink in Spain, seals in the US and cats in Poland. From 2003 to 2023, 873 human cases have been confirmed with 458 deaths, a mortality rate of around 50%, although it is estimated that in a potential large-scale outbreak it could be less lethal.

The chances of mutation

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the emergence of the 2020 variant has caused “an unprecedented number of deaths in wild birds and poultry”. Avian influenza poses “ongoing risks to humans,” about which there is “concern that the virus might adapt to infect humans more easily,” especially because of the possibility of a mammal acting as a vessel in which different types of viruses combine.

The US Center for Disease Control (CDC) considers the current public health risk to be low, a view shared by its European counterpart, the ECDC. The virus is still rarely transmitted to humans and even more rarely from person to person. Experts say it would take several overlapping mutations to increase airborne transmission and transmission to humans.

However, it has been shown experimentally that the influenza A/H5N1 virus can be adapted to allow airborne transmission between mammals, which may have occurred in Spanish mink, where at least one facilitating mutation has been detected. And as avian influenza is already considered panzootic (a pandemic in animals), the chances of mutation are increasing. Vaccination in animals and humans is currently being studied, and the evolution of the virus, other variants and non-H5N1 avian influenza are being closely monitored. The future is unknown.

Comments on this publication