As we continue this arduous journey through the pandemic of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which causes COVID-19, there is one destination we wish to reach: immunity. In the face of an iceberg that the world didn’t see coming, immunity is now that lifeboat in which we all hope to be rescued. However, this lifeline is uncertain. Achieving immunity through a vaccine doesn’t seem to be on the horizon yet, and, in the meantime, science is revealing that even immunity acquired by infection itself is not guaranteed. There are still some big unknowns: how strong the immunological memory of the virus is, how long it will last, or whether we will achieve so-called group immunity.

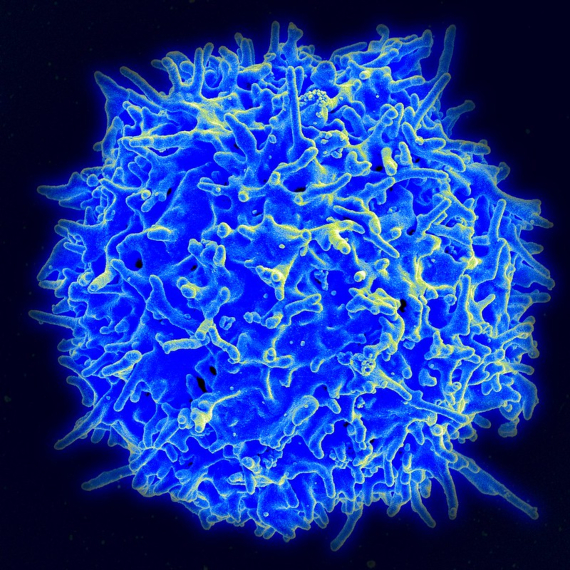

The immune system’s superpower is the ability to discriminate between the self and the non-self, to tolerate the components of our organism but to reject the foreign ones, and for this it has several lines of defence. The first is called innate immunity, made up of cells and molecules that trigger a rapid and non-specific response against any foreign element, while preparing the army of adaptive (also referred to as acquired) immunity. This is commanded by two legions: B-lymphocytes, producers of antibodies, and T-lymphocytes, also capable of specifically recognising the pathogen and killing it, as well as controlling other defences.

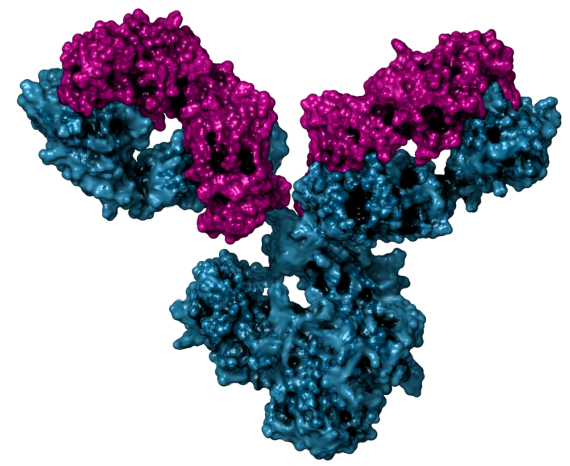

The antibodies, Y-shaped molecules that bind to different parts of the virus, act by selecting it for elimination, but some also block its entry into the cell; they are the neutralisers. In February, researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia, described the presence of antibodies in the blood of a patient with moderate symptoms, up to seven days after recovery. Other studies in China confirmed the production of antibodies, including neutralisers, 10 to 15 days after infection. Some are specific to SARS-CoV-2, while others may also recognise different coronaviruses such as those for colds, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

Reinfection

The appearance of antibodies is a marker to look at to check the immune response to a pathogen. Their production persists after the disease, so they also serve as witnesses to a past infection that can be detected in a test. But their presence is not necessarily a guarantee of immunity against reinfection. This depends both on their neutralising power and on the duration of the cellular clones that manufacture them, which can be limited (vaccines such as polio or smallpox protect us for life, while others give us only temporary protection).

In this regard, alarms were raised when news of recovered patients allegedly being re-infected with the virus began to arrive from China, Japan and Korea. However, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and other experts infer that what was detected in the tests probably corresponds to dead traces of the virus, still in the process of elimination. “The consensus is that these are not real reinfections, but rather the detection of remnants of the virus,” microbiologist and immunologist José Villadangos, of the Peter Doherty Institute, told OpenMind. “In any case, it shows that detection by PCR is not equivalent to the presence of infectious virus.” One animal experiment suggests that reinfection is not possible in the short term: researchers from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences have found that macaques remain immune to the virus for at least 28 days after infection, and at 42 days retain protective levels of neutralising antibodies.

Early to tell how long protection will last

But this does not mean that the immunity is complete or long-lasting. Regarding the former, an intriguing, yet unpublished study from Fudan University in Shanghai, China, found that ten young patients out of a total group of 175 of different ages, all recovered from mild COVID-19, produced only non-neutralising antibodies. As for the latter, it is too early to tell how long protection will last, although experts point to what they’ve learned about other similar viruses. “Right now, it makes the most sense to treat SARS-CoV-2 as another human coronavirus, and use what we know about those other viruses as temporary placeholders to fill in the gaps in what we know,” Texas A&M University virologist Benjamin Neuman, a coronavirus specialist, told OpenMind.

Neuman points out that “a person can have more than one human coronavirus at the same time, and immunity tends to be quite temporary, on the order of 1-2 years perhaps. “Antibody levels to the SARS virus have been shown to begin to decline after two years. “I think that it will behave the same as SARS and MERS, with waning immunity with time and better responses after severe infection,” coronavirus immunologist Stanley Perlman, of the University of Iowa, told OpenMind. In any case, and according to Neuman, what is already known “does not give much cause for optimism in terms of infections or vaccines generating long-term immunity.”

However, if antibodies are no guarantee of protection, then neither are antibodies the only protection. As explained, virus-specific T-lymphocytes are also an essential part of immunity, and are not measured in serological tests. In fact, for the immunologist from Imperial College London (UK) Daniel Altmann, this could be key: “For the related coronaviruses, immune memory seems more long-lived in the T cell compartment,” he tells OpenMind. The expert adds that this would explain how people with antibody deficiencies, for example those affected by hypogammaglobulinemia, have been able to recover from the disease. “It is still debatable whether neutralising antibodies should indeed be considered THE correlate of protection.”

Immunity passports

In any case, what is already known, and the unknowns that remain, call into question the creation of “immunity passports” for people who have already got over the disease, a concept studied by some governments and against which the WHO has already warned: “There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” the agency has said. In addition, uncertainty about the coverage and duration of immunity casts doubt on a widespread idea: the possibility of achieving group immunity.

The likelihood that a percentage of the population already infected can provide group immunity to the rest has been considered in view of the large number of asymptomatic infections. Altmann is sceptical: “If I had to guess the seroprevalence for the entire urban population of Europe, I’d put it no higher than 8%. That’s far off the 60-80% needed for protection.” In fact, adds Villadangos, new studies on the reproduction rate of the virus (R), which expresses the average number of people infected by each virus, raise it from around 2.5 to 6.

In short, answers are still lacking. Neuman points out that imminent studies may be able to solve some of the unknowns. But if, as Altmann fears, a second wave will not be gentler, perhaps we can only hope that subsequent waves will be, once the virus is among us for good, as virologist Klaus Stöhr, who led the WHO response against SARS, predicted to Nature. Stöhr foresees a future in which SARS-CoV-2, like the coronaviruses of the common cold, will return to infect us every year, but our partial immunity will protect us from its more harmful effects without the need for vaccines. “I think this is a good outcome, and perhaps desirable,” Perlman concludes.

Javier Yanes

@yanes68

Comments on this publication