While 19th century surgeons had a good grasp of human anatomy from the dissection of cadavers, their inability to see inside living bodies hampered their knowledge of the functioning of internal organs. The gruesome surgery of the day was not an option for in vivo observation and experimentation. But a gunshot accident that resulted in a bizarre wound—and the even more unusual doctor-patient collaboration that came about as a result—forever changed our understanding of how the human body works.

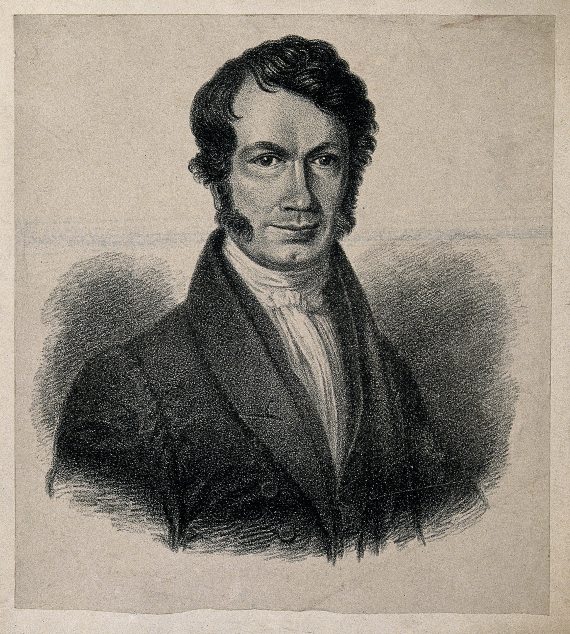

Doctors at that time who wanted to know what was going on “under the hood ” simply looked down the throat, felt with their fingers or listened attentively with a stethoscope. But that would change in the summer of 1822. On June 6 of that year, at the fur trading post on Mackinac Island in Lake Huron in Michigan Territory, a carelessly held musket accidently went off, shooting a healthy young French-Canadian voyageur and trapper named Alexis St. Martin in the chest from close range. The wound was so grievous that no one expected him to survive, but he was nevertheless attended upon by the closest doctor, William Beaumont, (21 November 1785 – 25 April 1853) a U.S. Army surgeon stationed at nearby Fort Mackinac. The doctor later wrote that he “found a portion of the lung as large as a turkey’s egg protruding through the external wound, lacerated and burnt; and immediately below this, another protrusion, which […] proved to be a portion of the stomach […] pouring out the food for his breakfast through an orifice large enough to admit the forefinger.”

These two men, Beaumont and St. Martin, surgeon and patient, could scarcely have been more different. Beaumont, descended from New England Puritans, was an ambitious and capable man, eminently practical, who sought position and wealth through hard work and thrift. In contrast, St. Martin, nine years the doctor’s junior, was an illiterate French-speaking Catholic from the backwoods of Quebec, lanky and strong, with a taste for liquor and a notorious reputation for rowdy behaviour.

For weeks after the accident, the French-Canadian trapper clung tenaciously to life, fighting off infections and a high fever. Everything he ate passed out through the hole in his stomach and he was kept alive “by means of nutritious enemas” administered by his attentive caregiver. But against all odds and to the surprise of everyone, the robust young man managed to pull through and begin his slow recovery.

A surprise survivor and a curious mind

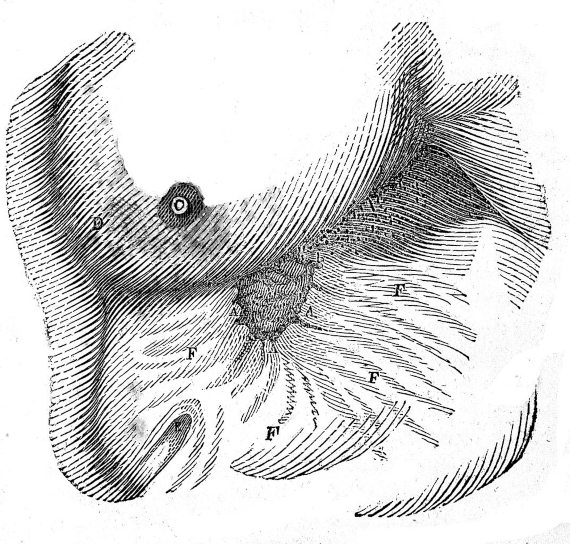

After many months of unsuccessfully trying to close the orifice through the application of pressure, Beaumont wanted to suture the lips of the wound, but St. Martin had already endured too many painful operations and refused to submit to the procedure. Nevertheless, the wound eventually healed by itself, with the edge of the hole in the stomach fusing to the opening in the skin and the lining of the stomach forming a kind of valve and “resembling a natural anus with a slight prolapsus.” This permanent gastric fistula, as it is medically known, prevented food from escaping but yielded under pressure from a finger, allowing direct access to the stomach. “On pressing down when the stomach is full, the contents flow out copiously,” noted Beaumont.

Having lost his employment with the American Fur Company due to his disability, and now penniless, St. Martin was in serious danger of being sent back to his native Quebec, a 2,500-km journey by boat. Beaumont, fearing that his patient would not survive the long voyage, took the young man into his home to care for him. By the spring of 1824, St. Martin had fully recovered his health, by which time he was working as a servant and handyman in Beaumont’s home. And the American surgeon, who recognised the scientific opportunity that fate had laid before him, would be free in the evening to perform experiments on his guest, the owner of the only stomach on earth that could be accessed directly from the outside.

Experimenting and observing without prejudice

Little was known at the time about the workings of the human stomach and the digestive system, and a debate raged in the medical community over the method by which the stomach digested food. Some theories suggested that a grinding or mechanical process was dominant, while others argued in favour of chemical processes, fermentation, putrefaction or disintegration by heat.

Having no particular theory to advance, Beaumont was free to experiment and observe. In an article published in The American Medical Recorder in 1825, he wrote, “this case affords a most excellent opportunity of experimenting upon the gastric fluids and the process of digestion. […] One might introduce various digestible substances into the stomach, and easily examine them during the whole process of digestion.”

While the frontier doctor was not an experienced researcher, he was diligent, observant and kept meticulous notes. His experiments, which were no doubt disagreeable and at times humiliating for St. Martin, initially consisted of attaching different pieces of food to string and inserting them through the stomach hole to measure digestion rates. In later experiments, Beaumont would open the hole and peer inside, noting the digestive process under a wide variety of situations. He threw himself into his experiments and went so far as to taste the gastric fluids and mucous coat of the stomach to try to determine their content. He also extracted large quantities of gastric juice to experiment with and sent samples to Europe for analysis.

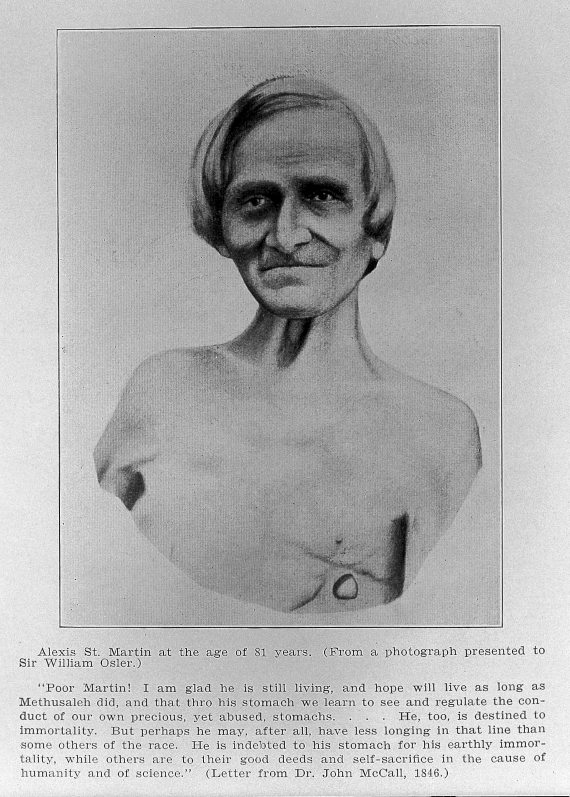

These experiments would continue in fits and starts while Beaumont was transferred from one frontier state to another before finally settling in St. Louis, Missouri. On one occasion St. Martin returned to Canada, where he re-entered the fur trade, married and had children, but his impoverished situation coupled with Beaumont’s unceasing entreaties persuaded him to return to the U.S., travelling over 2000 miles with his growing family in tow, to submit to more of the doctor’s intrusive experiments in exchange for payment.

As time passed, St. Martin grew weary of being a guinea pig and demanded more money. In 1832, in order to bring some legal certainty to the situation, Beaumont had St. Martin (who couldn’t read) sign a contract that he would “submit to…such physiological or medical experiments as the said William shall direct or cause to be made on or in the stomach of him, the said Alexis…and will obey…the exhibiting and showing of his said stomach.”

Digestion is primarily a chemical process

Finally, after more than 200 experiments carried out over eight years, this odd collaboration finally came to an end, and in 1833 the two men parted ways for good. St. Martin and his family returned to Quebec and a poverty-stricken existence, while Beaumont published his account of the experiments, Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion, a work that brought him the recognition and prestige he sought.

Beaumont drew many conclusions about the digestive process from his experiments, the main one being that digestion is primarily a chemical process, assisted by muscular contractions, thereby putting an end to the medical debate. He found that gastric juice contained muriatic (hydrochloric) acid and other enzymes and was secreted by the lining of the stomach in the presence of food. He discovered that meat or starchy foods were digested more quickly than vegetables and noted the importance of fibre in the diet. St. Martin’s love of eating and drinking showed that alcohol, as well as overeating, were causes of gastric irritation.

The “Father of Gastric Physiology” built his reputation on his ability to access the Canadian trapper’s unique stomach and until the end of his life he hounded St. Martin to move to St. Louis, Missouri, to continue the experiments. However, the fur trader never returned. St. Martin eventually fathered six children and died at the age of 86 in 1880, outliving Beaumont, who expired in 1853 aged 67 after slipping on ice-covered steps.

Comments on this publication