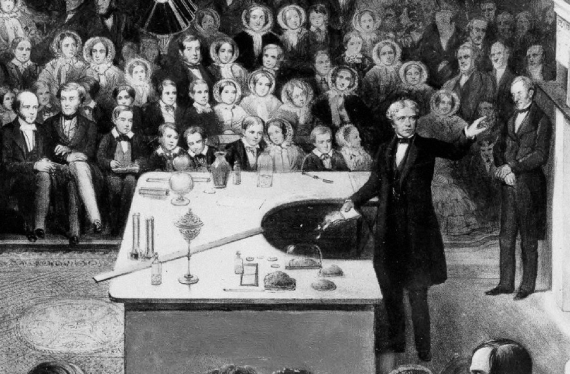

In mid-19th century London, one of the most important and eagerly awaited events of the Christmas season was the “Christmas Lectures”, the science outreach talks through which Michael Faraday made science available to (astonished and amazed) general audiences at the Royal Institution, beginning in 1825, the year he was appointed Laboratory Director of this scientific organisation. Faraday himself presented 19 of these Christmas lectures, including his most famous and best remembered talk, delivered in 1848 and entitled The Chemical History of a Candle.

Although the Christmas Lectures began in 1825, in reality their origin dates back to some years earlier, specifically to 1800. In that year, the illustrious scientist and aristocrat Benjamin Thomson (Count Rumford), together with other leading British scientists, founded the Royal Institution with the aim of spreading knowledge and new mechanical inventions and innovations, as well as teaching science and its application in everyday life through discussions, lectures and experimental demonstrations.

Problem 1: Lighting up the audience

Each person attending Faraday’s popular lecture is given a candle at the entrance. At one point, as part of the talk, the physicist mingles with the audience members while carrying a lit candle, and with it he begins to light their candles while inviting them to do the same with their neighbours’ candles. Each person who has a candle is asked to find someone whose candle is unlit and to light it for them until everyone present is holding a lit candle, a task that takes four and a half minutes to complete.

If it takes each person 30 seconds from having their candle lit to lighting a neighbour’s, how many people (including Faraday) have attended the lecture?

Although the Christmas Lectures began in 1825, in reality their origin dates back to some years earlier, specifically to 1800. In that year, the illustrious scientist and aristocrat Benjamin Thomson (Count Rumford), together with other leading British scientists, founded the Royal Institution with the aim of spreading knowledge and new mechanical inventions and innovations, as well as teaching science and its application in everyday life through discussions, lectures and experimental demonstrations.

Faraday enters the scene

In 1816 Michael Faraday gave his first talk, three years after he had started working at the Royal Institution as a laboratory assistant, under the guidance of his “patron”, the English chemist Humphry Davy. In 1821, Faraday was promoted to Assistant Superintendent of the Royal Institution Laboratory, which he finally took over in 1825.

Up to that time, those attending the lectures were mainly nobles and aristocrats, prosperous businessmen, merchants and other members of the burgeoning bourgeoisie. Undoubtedly motivated by his own humble upbringings, and taking advantage of his new position, Faraday initiated the Christmas Lecture series, conceived as a series of talks designed to bring science closer to the public in an exciting, surprising and engaging way, and open to all members of society, especially the young.

He began his most famous Christmas talk, The Chemical History of a Candle (1848), by announcing to the eager audience that “there is not a law under which any part of this universe is governed which does not come into play and is touched upon in these phenomena.” Faraday delighted the audience by describing the chemical reactions that were involved in the simple act of lighting a candle, while accompanying his remarks with demonstrative experiments such as placing a spoon at the uppermost part of the flame and then removing it and displaying the soot to demonstrate that when combustion was not complete, soot was produced, which was nothing more than tiny particles of blackened carbon.

Problem 2: A burning question

Just before starting his long-awaited lecture, Faraday lights two candles of equal length but different thickness. The thicker one is designed to last four hours and the thinner candle one hour less. When the talk is over, both candles are still burning and the thin one is exactly half the height of the thick one. How long has the talk lasted?

After Faraday’s retirement, the Christmas Lectures continued to be a fixture during the holiday season, an unmissable event for the youth of London that was only cancelled four times during the early days of the Second World War. Even before this forced break, in 1936 and almost simultaneously with the launch of television programming in Great Britain, the BBC included the Christmas Lectures in its broadcasts, which makes them one of the first shows ever televised and also one of the oldest television programs that remains on the air, given that they have continued to be broadcast with some regularity over the years, and each and every Christmas since 1966.

This regular coverage has made them one of the favourite Christmas programmes for Britons young and not-so-young alike. Their popularity has also been boosted by the fact that, over the years, they have featured such outstanding presenters as Carl Sagan and naturalist David Attenborough.

Problem 3: Duncker’s Candle Problem

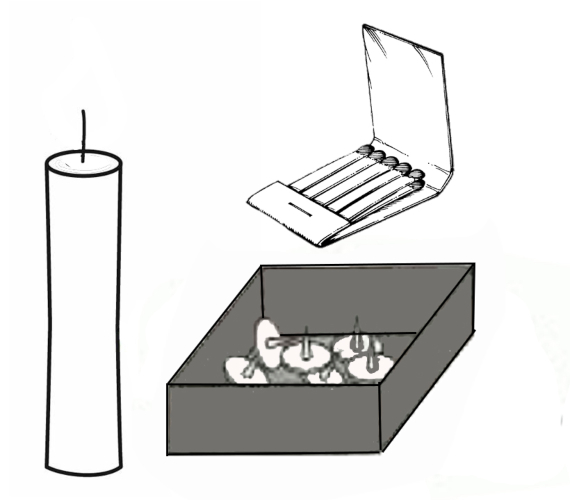

Returning once again to Faraday’s (most) famous Christmas lecture, one of the experiments he did not carry out is the so-called “Candle Problem“—which is quite understandable since it was not described until almost a century later, in 1945.

The problem in question, whether seen as an experiment or a puzzle, was devised by German psychologist Karl Duncker and consists of the task of lighting the candle in such a way that it does not touch the table or spill wax on it, using only the elements arranged on it: a book of matches and a box of thumbtacks.

This puzzle or challenge brings into play the creativity of the person faced with it—as well as his or her dependence on functional fixedness. And although there is an “official” or standard solution, in reality it is an “open” problem in the sense that it may have other possible and imaginative solutions.

Solutions

Comments on this publication