In the complex world of conspiracy theories, there is something for everyone. But just as the idea that the Earth is flat and they are hiding it from us is nonsense to the vast majority of humans, other theories have gained so much acceptance that they have become integrated into popular culture. One of the most obvious examples is planned obsolescence, the alleged strategy of companies to manufacture products of low durability in order to force us to acquire new models and thus maintain our high consumption levels. However, here too, it is worth approaching the idea with a critical eye, because perhaps not everything is as simple as an conspiracy by big business to empty our wallets. If planned obsolescence does exist, according to engineer and writer Bob Baddeley, it is also “your fault.”

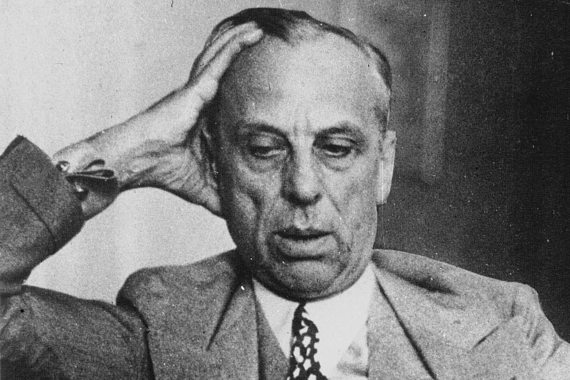

The history of planned obsolescence dates back to the 1920s, when General Motors president Alfred P. Sloan devised a strategy to compete with the rival auto giant, Ford. Faced with Henry Ford’s efforts to flood the United States with his model T, which was progressively improved so that new customers could have access to a better version, Sloan wanted those who already owned a GM car to exchange it for the latest model when the previous one still worked, simply because they felt “a certain dissatisfaction with past models compared with the new one.”

The Great Depression and the manufacturers of light bulbs

Sloan applied to his cars the concept of the annual model, which was how the bicycle industry operated. However, the initial vision didn’t focus on low durability; GM’s president used the term “dynamic obsolescence,” since his intention was that consumers themselves would see their car as obsolete compared to the new models and replace it even if they didn’t need it. It was the real estate agent Bernard London who in 1932 suggested in an article a way to stimulate consumption in order to weather the Great Depression: “To chart the obsolescence of capital and consumption goods at the time of their production.” In his title, London used an expression that perhaps by then was already circulating in the business community: “Planned obsolescence.”

However, some had already arrived at this idea before London’s proposal, putting into practice a limitation on the useful life of products. In 1924, a meeting of the main manufacturers of light bulbs in Geneva gave birth to the Phoebus cartel, whose objective was to divide up the world market. This organisation also established a standard for the useful life expectancy of light bulbs: 1,000 hours, as opposed to the 1,500 or 2,000 hours that had been common until then. The cartel fined those who manufactured products with a longer life. But while Phoebus has commonly been accused of being driven solely by the purpose of increasing light bulb sales, engineers believed that after 1,000 hours, efficiency dropped and energy waste increased, and certain accusations against the cartel of reducing bulb lifespans for profit were dismissed.

Today, the idea has spread among consumers that the large technology multinationals have widely adopted the strategy of manufacturing low-durability devices to force us to buy new models. But Baddeley teaches us a lesson from his own experience. As an engineer, he participated in the development of a product that had a non-replaceable button battery, a frequent cause of obsolescence. However, the expert points out that this decision was in response to demand from consumers themselves: “We couldn’t get the users to be interested in keeping the device running longer than the battery lifetime,” he says, among other reasons.

The seduction of the new

For many experts, the key is that we have all succumbed to the seduction of the new that Sloan was able to foresee; planned obsolescence not only responds to the industry’s desire to sell more, but also to the consumer’s desire to own the latest model. For Baddeley, “the entire conspiracy is explained away when you consider that manufacturers are giving consumers exactly what they’re asking for, which is often compromising the product in different ways. It’s always a trade-off.” Yale University economics professor Judith Chevalier explained to the BBC that companies react to consumer tastes, and that planned obsolescence is not simply a deception by manufacturers, but in certain situations the fault lies with consumers, who do not value a more durable product, but one that possesses the latest technology.

Even Canadian author Giles Slade, whose 2006 book Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America helped fuel the popular outcry against planned obsolescence, has recognised that the current consumer model has raised the quality of life like never before in history. But that outcry also has its own dark side, as shown by the fact that certain light bulbs touted as being almost eternal by supposed champions against planned obsolescence have now been deemed fraudulent; in this case, the conspiracy theory itself served as a juicy sales pitch.

It is no coincidence that one of the myths surrounding planned obsolescence also refers to a light bulb; the Centennial Light, the famous bulb from the Livermore-Pleasanton fire station in California, has been shining almost continuously since 1901 without ever burning out, and even has its own webcam. The California light bulb has become the icon of the movement against planned obsolescence — proof, some say, that it is possible to make products that last a lifetime.

However, here again the legend is not so clear cut; a study of the bulb determined that the filament, made of carbon instead of the tungsten that would later become widespread, is eight times thicker than normal, making it difficult to burn out. But such thickness comes with a downside, great energy inefficiency; it is thought that its brightness was originally about 30 watts, while today it shines with only four watts, scarcely equivalent to the glow from a tea candle. While the Centennial Light is undoubtedly a venerable survivor from the times before planned obsolescence, it is not the type of product anyone wants to buy today.

Comments on this publication